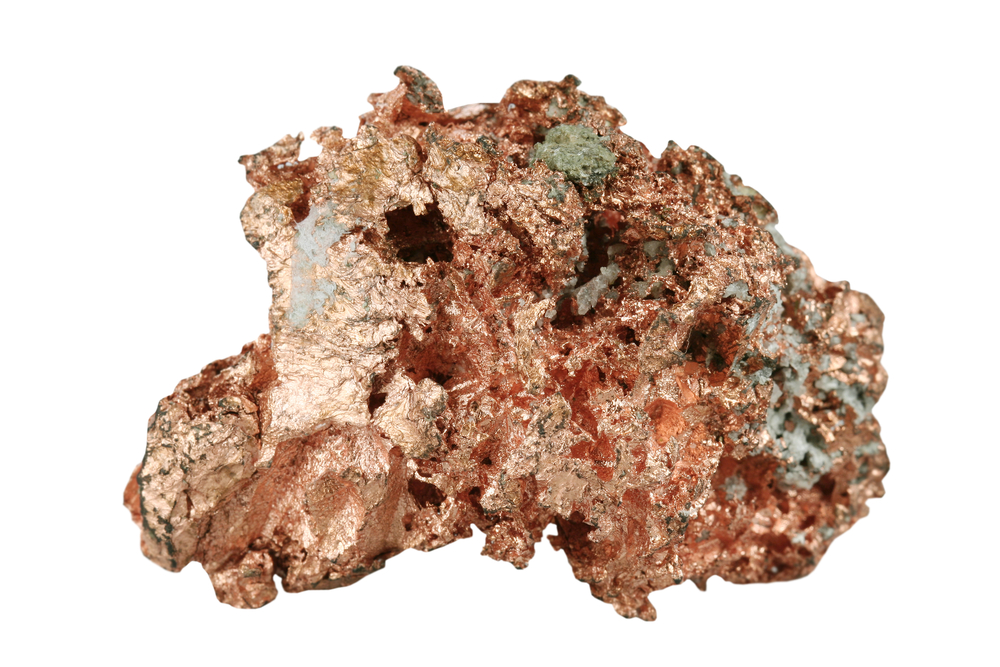

Prostate cancer cells have the capacity to scavenge and pile copper, an essential element for the proper function of the human body.

Prostate cancer cells have the capacity to scavenge and pile copper, an essential element for the proper function of the human body.

However, recent results from a study by Duke Medicine researchers have unveiled a way of turning cancer’s copper scavenging into a deadly activity for the tumor itself.

The team, whose results titled “Copper Signaling Axis as a Target for Prostate Cancer Therapeutics” were published in The Journal of Cancer Research, managed to deliver a trove of copper together with a drug that selectively destroys the diseased cells filled with the mineral, leaving healthy cells untouched.

This experimental approach took advantage of two drugs already used in the clinic. Among them, disulfiram, a drug approved by the FDA to treat alcoholism, that relies on the additional copper found in prostate cancer tumors. Once used for the treatment of prostate cancer, its poor results in clinical trials among patients suffering from an advanced form of the disease stopped it from moving forward.

“This proclivity for copper uptake is something we have known could be an Achilles’ heel in prostate cancer tumors as well as other cancers,” Donald McDonnell, Ph.D., chairman of the Duke Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology and senior author of the study said in a Duke press release.

“Our first efforts were to starve the tumors of copper, but that was unsuccessful. We couldn’t deplete copper enough to be effective,” said Dr. McDonnell. “So we thought if we can’t get the level low enough in cancer cells to kill them, how about we boost the copper and then use a drug that requires copper to be effective to attack the tumors. It’s the old if-you-can’t-beat-‘em-join-‘em approach.”

The researchers found that the amount of copper the cancer cells store is not enough to render them sensitive to the drug. As such, the team added a copper supplement together with disulfiram, resulting in significant reductions of tumor growth in animal models of advanced prostate cancer.

Furthermore, the results showed that androgens increase copper levels in the cancer cells, which means that men who have been on hormone therapies that have failed to slow tumor growth can particularly benefit from disulfiram and copper combination treatment.

“Unfortunately, hormone therapies do not cure prostate cancer, and most patients experience relapse of their disease to a hormone-refractory or castration-resistant state,” McDonnell added. “Although tremendous progress has been made in treating prostate cancer, there is clearly a need for different approaches, and our findings provide an exciting new avenue to explore.”

“While we did not observe significant clinical activity with disulfiram in men with recurrent prostate cancer in our recent clinical trial, this new data suggests a potential way forward and a reason why this trial did not have more positive results. Further clinical studies are now warranted to understand the optimal setting for combining copper with disulfiram or similar compounds in men with progressive prostate cancer, particularly in settings where the androgen receptor is active,” said Andrew Armstrong, M.D., associate professor of medicine, who was involved in a clinical study at Duke testing disulfiram in men with advanced prostate cancer.