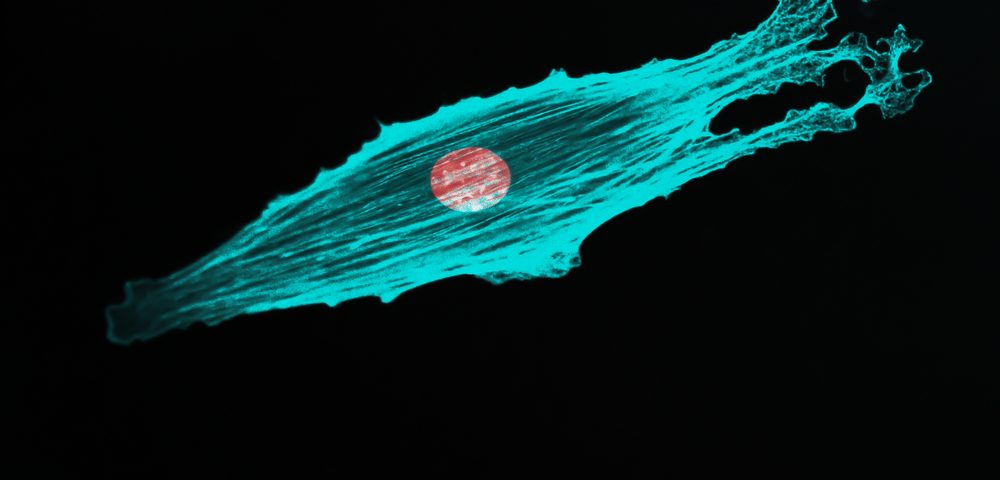

The cytoskeleton, a dynamic set of filaments that controls the shape of cells, plays a key function in the spread of prostate cancer cells to distant organs to establish metastasis, according to a recent study.

British researchers at King’s College London have found that a pathway that controls cell shape changes in response to a homing signal. Blocking this pathway in lab-grown prostate cancer cells hampered their ability to invade.

Their study, “The drebrin/EB3 pathway drives invasive activity in prostate cancer,” was published in Oncogene.

“Prostate cancer cells are attracted to the tissue they invade by homing signals released from these tissues,” senior author Phillip Gordon-Weeks of the college’s Centre for Developmental Neurobiology said in a press release. “We’ve now identified the cellular machinery that guides this process and we think these homing signals could one day be disrupted therapeutically to stop cancer cells escaping the primary tumour and invading the body to form secondary tumors.”

The team knew that the drebrin/EB3 pathway was involved in the migration of neurons. Because cell migration is important for cancer progression, they sought to investigate whether this pathway could also be involved in cancer cell migration.

Researchers found that lab-grown prostate cancer cells had high levels of drebrin compared to normal prostate cells. This protein was mainly found in contact with the cytoskeleton filaments, particularly in areas of high CXCL12 — a chemokine believed to play a role in forming prostate cancer bone metastasis.

Using 3D in vitro models of prostate cancer, the researchers saw that inhibiting the drebrin/EB3 pathway using the small molecule inhibitor BTP2, reduced the invasion of prostate cancer cells. They observed similar findings when the cells were engineered to lack drebrin or EB3.

Together, the findings suggest that this pathway is key for prostate cancer cells to respond to the homing signals, like CXCL12, and migrate towards such cues, entering the bloodstream and reaching distant organs to form metastasis.

Dysrupting this pathway could prevent prostate cancer from spreading to other regions of the body. In addition, knowing which men have an overactive drebrin/EB3 pathway may help doctors identify those more likely to develop metastasis.

“This research provides a really compelling example of how basic research can drive and inform translational research,” said Gordon-Weeks. “Using animal models, we now need to examine how the prostate cancer homing signal could be manipulated using treatments.”