Scientists at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center discovered that a protein called AIM1 keeps prostate cancer cells from acquiring properties that allow them to invade and spread within the body.

Cells lacking this protein have an unnatural ability to modify their shape and squeeze into other organs, where they originate new metastasis.

The study, “AIM1 is an actin-binding protein that suppresses cell migration and micrometastatic dissemination,” was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The study began with researchers analyzing available data about the genetics and chemistry of prostate cancer. They found that a particular gene, called AIM1 (short for absent in melanoma 1), was absent in 20-30% of non-metastatic and about 40% of metastatic prostate cancers.

AIM1 protein levels were twofold to fourfold lower in metastatic prostate cancers than in normal prostate cells and in prostate cancers confined to the gland (non-metastatic). The results suggested that AIM1 is associated with the ability of prostate tumor cells to spread and disseminate.

While prior studies had linked AIM1 to skin cancer development, its role in other cancers, including prostate cancer, was unknown.

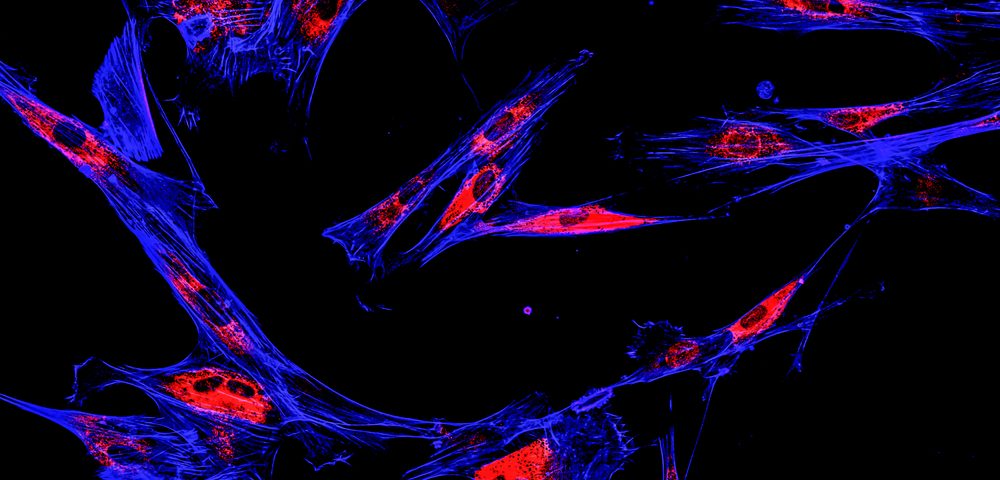

Researchers tracked the location of AIM1 in human cells grown in the lab using fluorescent dyes. In normal prostate cells, AIM1 was located close to the cell membrane, bound to another protein called beta-actin. Beta-actin is a key constituent of cells’ cytoskeleton, a network of filaments that determines a cell’s shape, among other functions.

But in prostate cancer cells, AIM1 was no longer located at the membrane and was free from its binding partner, beta-actin. This pattern of dislocation was confirmed in human prostate tissue samples, including in 87 localized prostate cancers and 52 prostate cancers that had spread to the lymph nodes.

“It appears that when AIM1 protein levels drop, or when it’s abnormally spread throughout the cell instead of confined to the outer border, the prostate cancer cells’ scaffolding becomes more malleable and capable of invading other tissues,” Vasan Yegnasubramanian, MD, PhD, associate professor at the Kimmel Cancer Center and an author of the research, said in a press release.

To confirm their hypothesis, the researchers teamed up with Steven An, an expert in cellular mechanics and associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. They looked at the physical properties at the single cell level of prostate cancer cells lacking AIM1.

Researchers found that cells without AIM1 had suffered an extensive remodeling. They also exerted three to four times more force on their surroundings than cells with normal AIM1 levels. This is commonly seen in cells with metastatic potential, or high potential to migrate and invade.

Prostate cells lacking AIM1 were indeed capable of migrating to empty spaces in a dish, or even invade through materials mimicking our own connective tissue, at much higher rates than cells with normal levels of AIM1.

This was confirmed in animal models, where cells without AIM1 were able to spread to other tissues 10 to 100 times more than prostate cancer cells with normal levels of AIM1. But despite their ability to migrate, these cells were unable to establish metastasis, suggesting that other factors are involved in the spread and growth of metastatic prostate cancer.

“Our experiments show that loss of AIM1 proteins gives prostate cancer cells the ability to change shape, migrate and invade. These abilities could allow prostate cancer cells to spread to different tissues in an animal and presumably a person,” the study’s first author, Michael Haffner, MD, PhD, said. “It’s not the whole story of what is going on in the spread of prostate cancer, but it appears to be a significant part of it in some cases.”

In future research, scientists want to understand the mechanism that drives AIM1’s abnormal location in prostate cancers, which may help to identify new drug targets for preventing metastasis.