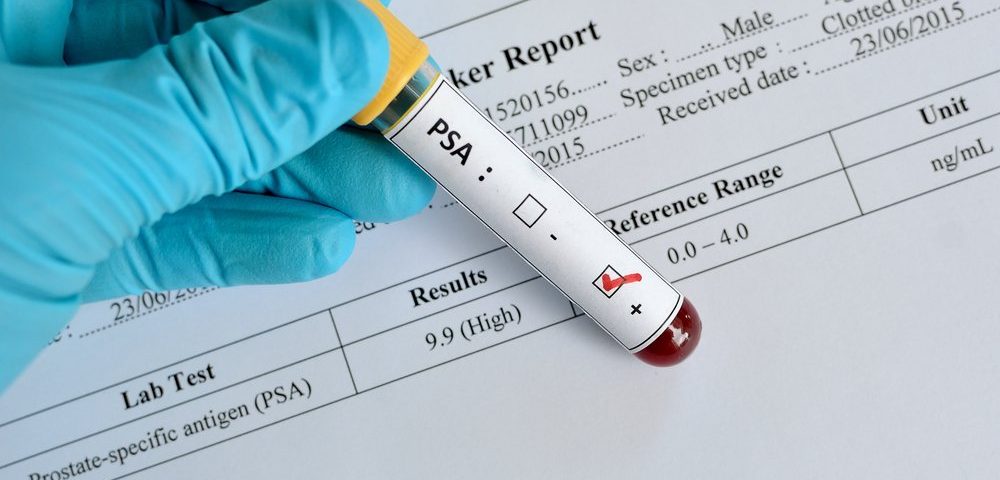

A blood test measuring the levels of PSA — a well-known marker of prostate cancer — cuts deaths from the disease by nearly 30%, the longest screening study on prostate cancer shows.

The study, “Improving Prostate Cancer Screening: 22-Year Follow-up in a Randomized Trial,” followed 20,000 men in Sweden for more than two decades and was featured in Maria Franlund’s PhD thesis.

“This research is important because it shows the long-term effects of an organized screening program in Sweden,” Franlund, MD, PhD in Urology at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and head of department at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, said in a press release.

There is no question that PSA screening detects prostate cancer about six years earlier than a digital rectal exam and 10 years before symptoms appear. However, whether to routinely screen men for their PSA levels remains one of the most controversial subjects of recent years among urologists.

The issue comes from not knowing whether PSA testing actually saves men’s lives, and whether the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of otherwise harmless cancers would be worth the risk. Thus, current guidelines in most countries worldwide suggest that routine PSA testing should not be offered alone for diagnosing prostate cancer.

Franlund’s research, however, challenges those recommendations.

The study was based on data from the Randomized Population-Based Prostate Cancer Screening Trial (ISRCTN54449243), which included 20,000 men living in the city of Göteborg in 1994.

Participants, between 50 and 64 years old at the time, were randomly assigned to receive a PSA test every two years — along with a biopsy if PSA levels were elevated — or to a control group not offered PSA screening.

After 22 years of follow-up, approximately 1,528 cancers had been detected in screened participants, compared to 1,124 in the control group. However, cancers in the screening group were detected at an earlier stage, which led to a 29% reduction in prostate cancer deaths. In total, 112 screened men died from the disease, compared to 158 deaths in the control group.

Researchers also identified three groups of men who had a particularly high risk of death because of prostate cancer: men whose disease was detected during the first screening, all of whom were 60 or older; men diagnosed after leaving the study; and men who were invited to the screening group, but did not participate.

This last group of men, called the non-attenders, had a lower incidence of prostate cancer than attenders — most likely because asymptomatic, low-grade cancers were not detected — but were more than three times more likely to die of the condition.

Researchers also noted that men diagnosed after the study’s termination were less likely to receive curative treatments — likely because their were older and less likely to endure aggressive treatments — suggesting that screening programs should start earlier.

“This investigation reveals that the men at high risk of PC death were those who were invited, but did not participate in the program, those who started screening after age 60, and those who had a long life expectancy and terminated screening too early,” Franlund stated. “To improve a future screening program, these findings must be regarded.”